I consider myself a relatively well educated individual – holding both undergraduate and graduate degrees. I’m relatively well read – with history being one of my favorite topics – and I work to stay informed on current affairs. I’ve lived for 10 years in Asia and have served overseas as a Diplomat. Even with all that, it never ceases to amaze me just how much I don’t know. One of my favorite topics has always been the Second World War – a topic on which read extensively – I consider myself reasonably well versed. As I started into this book, however, I quickly realized that my education came to a hard stop on or around August 14, 1945 – VJ Day – the day on which Japan’s unconditional surrender was announced.

I decided to pick up a title on the Korean War while watching the Winter Olympics. I started into “The Coldest Winter” by David Halberstam but found the first few chapters a little disorienting due to the fact that it begins well into the conflict. I switched to this title – “The Forgotten War” – by Clay Blair and found it to be a much better jumping off point since it provides more historical and political context. I’m about a third of the way through the book and wanted to share a few initial thoughts. I’ll caveat everything that comes after by saying I know very little about this time in America’s history – anything I write will be based only on what I’ve learned from a single book.

First take-away – the U.S. was completely unprepared for this conflict. It was eye-opening for me – the speed and degree to which the United States demobilized after the end of WWII. In a short period of 2 – 3 years, Harry S. Truman presided over the dismemberment of what was arguably the most powerful military organization this world had ever known. Blair describes a President whose desire to decrease the federal deficit, combined with a dislike or distrust of the professional military establishment, led him to decimate both branches of the armed forces. By 1948, the United States was a nation with significant global commitments, facing significant perceived geo-political challenges, coupled with minimal ability to support those commitments. Combine that with a residual over-confidence flowing from our victory over both the Germans and the Japanese and you had the makings of a perilous situation.

Second take-away – the U.S. came out of the Second World War without a clear vision for what it wanted to be in the post-war world. While the book only touches lightly on these topics, it does describe a dysfunctional relationship between the Service Chiefs and the Truman’s 2nd Secretary of Defense – Louis A. Johnson – a relatively toxic relationship between the Army and Navy in an era of rapidly shrinking budgets and messaging miscues to Russia and North Korea on the part of both State and Douglas MacArthur – who all too often took it upon himself to opine independently on U.S. foreign policy. All we knew was that we were apprehensive about what we saw as the rise of a monolithic, global communist movement led by the U.S.S. R.

With the notable exception of the current Administration, we as Americans have come to expect a foreign policy rooted in well-thought out, principled positions, built upon international alliances, enabled by the exercise of soft power and backstopped by overwhelming military power. None of that was true for the United States of 1950. We were still a relatively new global power – just beginning to build the capabilities and institutions – economic, military and diplomatic – that would help to define the post-war world. We had not yet established the foreign policy construct(s) that spoke to situations like Korea. Nevertheless – or maybe as a result – when North Korea invaded the South on June 25, 1950 – the U.S. was relatively quick to intervene despite the fact that U.S. government that had not identified the Korean peninsula as a strategic priority. In the face of a perceived global Communist threat – facing criticism from Republicans at home that he was soft on Communism – with assurances from his military leaders – particularly MacArthur – that this would be a simple and easily won conflict – it became all too easy for Truman to decide to intervene.

Third takeaway – we were blithely unaware of just how unprepared we were for a conflict of this type. Our disregard for the possibility that a small country like North Korea could field a capable military organization led everyone to believe that the mere entry of the U.S. military would result in a quick end to what everyone expected to be a brief and bloodless conflict. It didn’t take long for the North Koreans to disabuse us of this notion as they decisively drove both the Republic of Korea and U.S. militaries back to that small enclave in southeastern Korea which became known as the Pusan Perimeter. The military situation became serious enough – quickly enough – to cause U.S. military and political leadership to begin discussing the possibility of a U.S. Dunkirk.

Final takeaway from the first third of the book – we did regain control of the situation and managed to blunt the North Korean advance – stabilize the Pusan Perimeter – but not by superior generalship or military brilliance. As our area of control contracted, we benefited from interior lines of communication, we mobilized and deployed every military resource we had into the conflict, we took courage from desperation and we ground the North Koreans down.

Americans have, for quite some time, lived with an unshakable belief in the quality and capability of our military. That belief seemed to be just as strongly felt in 1950 as it is today. One of the things I appreciate about the portion of the book that I’ve read so far is an awareness of the degree to which this belief was effectively challenged in relatively short order. It had me thinking back to the events described in the first book of Rick Atkinson’s Liberation trilogy – “An Army At Dawn” – a really good history of the U.S. military in WWII. That book describes our entry into the war against Germany and the fighting in North Africa. In a very similar way, we threw poorly trained and equipped soldiers into battle against a motivated, experienced, well equipped enemy with all too predictable results. One of Atkinson’s themes is that any army has to learn to fight – learn to become a killing machine – and that the process of doing so is a painful and difficult one. You see the same thing happening in the first months of the Korean War and watching it happen – even on the pages of a book – is an agonizing process. As the war on the Korean peninsula progresses, incompetent leadership is exposed, inadequacies of training and equipment become obvious and our military learns to fight again – at great cost.

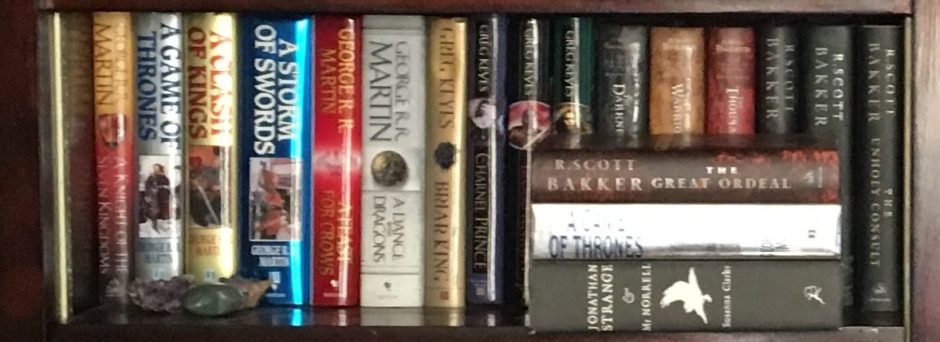

It feels good to put down the speculative fiction for a bit and pick up something like this. It’s not about the writing – it’s about what I’m learning. Still plenty to read and plenty to learn – I’ll update you as my education progresses.